Benjamin Ross’ new book, Dead End, offers a solid, insightful, and readable analysis of the structural causes of suburban sprawl, and the reasons why it remains difficult to build in urban areas despite renewed preference for urban living. Also, the book elaborates a hypothesis that status-seeking is the primary source of suburban “not in my backyard” opposition to infill development. I wrestle with this hypothesis – there is some truth in it, but it also weaknesses as an explanation and as the basis for a theory of change.

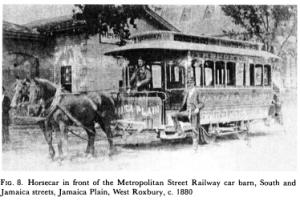

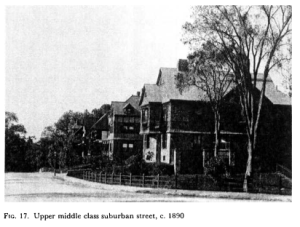

Ross traces the history of suburban land use policy – in which landowners have a high level of control over what their neighbors may choose to do – to the private covenants of socialist communes in the 19th century. The controls were institutionalized into zoning, when early suburban developments commercialized the form. The idealization of the countryside, the separation of residences from commerce, and the disdain for the city, also came from the idealistic, progressive reformers, a story that is also told in other histories of suburbia such as Crabgrass Frontier.

Early suburban developments were very clear about their intention to create high class, exclusive places, and these goals were explicitly institutionalized in law. The objective of keeping multi-family housing away from single family housing, in order to avoid degrading the single family housing, was explicitly cited in the Supreme Court decision on a case about Euclid, Ohio, which institutionalized what became known as “Euclidean Zoning. “…

…the development of detached house sections is greatly retarded by the coming of apartment houses… in such sections very often the apartment house is a mere parasite, constructed in order to take advantage of the open spaces and attractive surroundings created by the residential character of the district. Moreover, the coming of one apartment house is followed by others, interfering by their height and bulk with the free circulation of air and monopolizing the rays of the sun which otherwise would fall upon smaller homes…

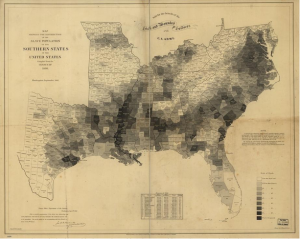

When policies were instituted to encourage home ownership during the Depression and after WW2, the mortgage criteria favored the suburban format, giving higher ratings to places that are new, that do not have a connected street grid, that have front lawns. Mortgage underwriting required cities to have zoning that segregated by density, keeping single family homes away from multi-family buildings, and that segregated by race. Dead End touches relatively briefly on the role played by race; this reading list compiled by Atlantic writer Ta-Nehisi Coates has extensive coverage of the role that racism played in housing policy.

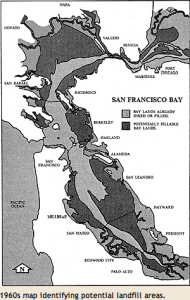

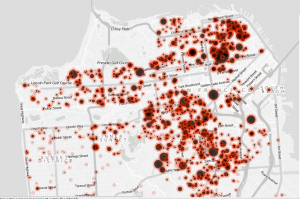

Ross does a good job of explaining how the familiar forms of residentialist neighborhood organizing got started with revolts against urban freeways and “urban renewal” projects which tore down functional working class neighborhoods, separated neighborhoods with barriers and safety hazards, and replaced lively streets with suburban style towers in parks. (In the San Francisco Bay Area, another crucible that forged the culture of neighborhood organizing was the environment activism which preserved San Francisco Bay and the hills from development.) In New York, the movement for historic preservation sparked by the failed battle to save Penn Station created legal tools that were later repurposed to spare ordinary old buildings and prevent change.

These neighborhood organizing movements rightly viewed unchecked development and top down planning designed to prevent and ignore public input as the enemy. This perspective calcified into perpetual opposition to neighborhood change. Existing residents have great power to reject or minimize new development that would reduce the prestige of the neighborhood, such as adding multi-family residences, improving sidewalks, striping bike lanes, building on parking lots, and other infringements on the ideal single-family vehicle-centric suburban design.

Problem of status

The book provides robust documentation for its argument that early suburbs were designed to promote class exclusivity and social status, and as well as for the trends whereby classic suburban forms were mass-marketed in the form of Levittowns and the proliferation of tract housing, designed to keep out the working class and poor.

Ross elaborates on the hypothesis that the desire to protect social status explains the growth and persistence of neighborhood organizing to keep out new development. The book plainly uses the term “Nimby” to describe the politically organized homeowning neighbors who organize again and again to preserve the neighborhood form and stop proposed change.

According the the book’s hypothesis, nimbies are primarily motivated by desire to maintain and increase social status, however it would be politically unacceptable to be upfront about this motivation, so nimbies use other arguments – environmentalism, historical preservation, traffic – as fig leaves to hide their naked self-interest. Not only do nimbies attempt to conceal their true motives from policymakers and fellow citizens, they can successfully conceal their self-interested motives even from themselves.

The pretexts used to hide nimby self-interest can include seemingly progressive goals; in some cities, nimbies ally with progressives to fight the displacement of low-income neighbors – and in so doing, they successfully protect the form of their existing neighborhood. Ross argues that “the striving to keep out people of lower status could be portrayed as a revolt of the oppressed people against rapacious capitalists, status-seeking disguised a cloak of self-righteous egalitarianism.”

There are several problems with these allegations of hypocrisy, disingenuousness, and false consciousness. While there may be some truth to the allegations, accusing an opponent of disingenuousness leaves no opening for compromise solutions. For example, neighbors have successfully fought potential development on the large parking lots at the Ashby BART station, in order to preserve the parking lot as precious “open space.” This may be driven in part a desire to keep out riffraff who would live in apartment buildings on the parking lot land. But when discussing the topic on Twitter, a friend brought up the weekend flea market held on the parking lot that community members want to preserve. Is there some other way to save the flea market? If you think of people in a public discussions as hypocrites deluded by false consciousness, you can’t make any progress addressing reasonable concerns.

There is another problem with diagnosing one’s political opponents as disingenuous and self-deluded. It opens the door to psychological diagnoses from the other side. For example, millennials prefer urban areas and less driving because they are fundamentally immature. But clearly they will grow out of preferring urban living, so there is no point to addressing their interests. Urbanists may think they value cultural diversity, but are actually just foodie snobs at odds with the values of real Americans..

Another challenge with the use of status as an all-purpose explanation for the passion behind nimbyism is that the definition of status itself changes over time, and is different among different subcultures. Ross does a good job of describing a change in the concept of status after the 60s, when ideas about exclusivity conveying status were replaced in some circles with the concept of authenticity, so that it becomes important to protect the neighborhood coffee shop and keep out Starbucks, for example.

So, what happens when the concept of status changes? While some suburbanites fear and disdain proposed 4-6 story midrise buildings as incipient slum towers, there are also snob urbanites with a corresponding disdain for places outside the big cities, San Franciscans who wouldn’t be caught dead in Mountain View or Redwood City. Isn’t it also true that some people who want to live in the city are also doing so for reasons of perceived status?

According to a progressive/bohemian esthetic, status can mean preserving the downscale. A local flea market is seen as a sign of authentic local culture and community-building, though it is a venue for the sale of unfashionable, dingy and discarded objects. Preserving the status of the downscale, from this perspective, can mean opposing changes that would benefit the health, happiness, and safety of local residents, such as like street trees and bike lanes.

Arguing that people organize to oppose change because they believe that what they have already is of higher value than the proposed new things is ultimately tautological. People value what they value.

Fear of traffic

There are other explanations to nimbyism that suggest alternative theories of change. The fear of traffic is one of the most common reasons given for nimby opposition to development. Until the implementation of a California law passed last year traffic as measured by motorist delay at intersections has been considered a negative environmental impact under the California environmental quality law, so opposing increase in motor vehicle delay can be an effective strategy in fighting new buildings.

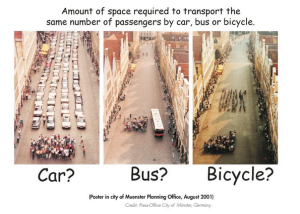

Ross considers concerns about traffic to be entirely disingenuous, a transparent pretext for opposing the building of new buildings to protect the status of the neighborhood. The problem is that in car-centric suburban areas that are starting to retrofit to become more walkable and transit-friendly, the legacy policies governing street design and vehicle parking actually encourage people to drive. Unless changes are made to policies and incentives, people who are afraid of excess traffic and parking overflow are likely to be correct. The policies and incentives need to change, so that fewer people are likely to drive in the new buildings. Persuading people that it is possible to reduce driving may help reduce fear of new buildings.

So an alternative to the hypothesis about status and false consciousness is a hypothesis that many people have expectations shaped by a lifetime experience and belief in the value of easy driving everywhere. Billions of dollars in advertising over decades have fostered a perception that cars mean freedom, long after the experience of driving had become a traffic-clogged annoyance.

Vehement efforts to protect low density development can reflect an attempt to return to a bygone era when it was possible to easily drive everywhere with Beach Boys on the radio. But traffic congestion is a mathematical inevitability when many people live in places with low density, separated uses, and traffic is funneled into the same few arterials and freeways. Where streets are designed for the primary purpose of moving cars quickly, it is unsafe to bike and walk, and even more people drive. If you provide plentiful enough parking for everyone to find a convenient space at every destination, then the result is vast amounts of land used for parking, making places ugly and unpleasant for walking.

There is a major shift in the works, partly cultural and partly generational – toward preferring a lifestyle with less driving, which means places that are more walkable, with destinations closer together, which is to say places with more density. But many people, especially baby boomers who grew up in the old paradigm, still expect and value the ability to drive everywhere. Time is on the side of walkability. In the community where I live, many of the fiercest opponents to improvements for walking and bicycling won’t be driving in a decade and will be demanding better facilities for walking and public transit.

Changing perceptions of status

If one considers that the concept of status is somewhat malleable, and that many studies show there is pent-up demand for walkable places, different strategies for change come to mind. In places on the Peninsula that have successfully re-urbanized downtown areas, there was extensive public involvement exploring design options, and a majority of people ultimately preferred the reinvention of downtowns into more pedestrian friendly places with more workers and residents, more amenities within walking distance, and less driving per person.

It may be possible to shift perceptions about the value of less driving. Events such as Bike to Shop day help people do more of the tasks of everyday life without a car, and appreciate changes that help people swap car trips for bike trips. When people depend on cars for fewer trips, and value easy bicycling and walking access, they may appreciate having buildings closer together, with less parking supply. Because the shift in values is in part generational, baby boomers who see their children leading carfree or carlite lifestyles have lightbulb moments when they realize that more people are starting to prefer more compact and walkable places – even if the baby boomers are still preferring to drive.

It may even be possible for people who say they value diversity to take actions to protect and increase diversity, by making decisions to add housing of various types in a community. The strategy here is to build on values that people say they have, and to build a working majority of people with those values.

Rail as a silver bullet

The book’s focus on status feeds into a theory of change that rail is key to the transformation of suburban places. Ross was a leader of Maryland’s decades-long initiative to build the Purple Line, a proposed 16 mile light rail extension to the Washington metro system.

In much of American culture, trains are perceived as high status, and buses as low status. This hierarchy is seen by some transit advocates as a reason to promote rail, since rail’s higher social status makes it more popular. Meanwhile, others with a more populist perspective see buses as the preferred transportation of lower income users, and therefore want to promote bus transportation instead.

I think that using a status argument for either bus or rail is misguided. Rail and buses are different technologies that are have different strengths and weaknesses. For the Purple Line, which is forecast to carry 74,000 passengers when it starts operation in 2020, buses won’t provide enough capacity, which Ross correctly points out. For other routes where the transit usage is robust but not that high (such as the VTA 22/522 with ~13,000 average weekday riders) a bus rapid transit system might be a better fit. Either rail or bus can be used for backbone rapid transit service depending on capacity needs; while bus service can be used for connecting service to the backbone lines.

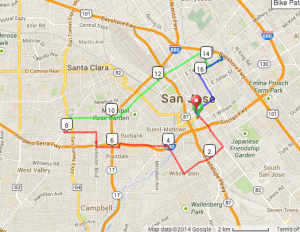

Plus, rail systems with poor transit design and land use deliver reduced benefits regardless of the supposed prestige of rail. VTA light rail has been excruciatingly slow for its first decades of existence, was oddly located and took decades to begin to trigger transit oriented development. BART was extended to suburbs, with stations surrounded by vast parking lots. After four decades, the BART station in Union City has recently added is a set of big apartment buildings, a half-mile walk from an inhospitable arterial intersection hosting acres of parking lot-surrounded strip malls. Development near transit, yes, but not nearly a walkable, human-friendly place.

Ross also argues that rail transit will naturally lead to the adoption of complete streets. The natural experiment of BART in the suburban east bay belies the argument that rail transit inevitably creates walkable, bikeable places. BART stations were surrounded by huge parking lots, in the midst of a suburban land use pattern with separated residential and commercial development connected by deadly multi-lane arterial roads. Even now, some East Bay jurisdictions resist street safety improvements that might slow vehicles.

Tactically, the Purple Line advocates were right to advocate rail for the Maryland corridor. Given the local culture and continued effective advocacy, it may well be the case that the Purple Line station areas will be well integrated with nicely walkable transit oriented development with streets that are safe and convenient for walking and bicycling. But that individual case is not necessarily universal. As with East Bay BART and VTA light rail, steel wheels don’t automatically translate into livable communities with safe pleasant streets.

Policy and strategy directions

Ross offers various policy proposals to make it easier to create more urban places, including removing parking requirements, and providing more funding for affordable housing. He proposes strong versions of both of these proposals, wanting to see parking gone altogether, which requires superb transit in order to work. He wants to see greatly increased federal funding for transit, this would require major transformation in national politics, where the R-dominated House votes consistently against transit spending. Given the fact that the greatest demands for affordable housing and transit are in economically booming metros, I suspect that a greater proportion of the investment is going to need to be driven locally.

Ross proposes greater regionalization of land use policy, to counteract the control exerted by homeowners in small suburban jurisdictions. While Maryland does have county-based land use regulation, Ross also reports that this regional structure also promotes slow-moving bureaucracy and sometimes corruption. Even moderately integrated transportation and land use policy in the Bay Area has sparked fierce opposition – time will tell whether the current level of coordination will work over time, and whether the state will provide the missing transit and housing funding to make the goals work, or whether opposition will undermine the plan’s implementation.

Recommendation

I recommend the book for people who are interested in the history and politics of cities and suburbs. Even if you have read other books on the origins of suburbia, you will likely learn from this one. The analysis of the politics of suburban neighborhood opposition to change is provocative, and serves as an interesting starting point to analyze and debate cause for the current state of affairs and theories of change.