Just read Ray Oldenburg’s sociology classic “The Great Good Place”, which names and praises the “third places” where people go between home and work. Oldenberg makes the case that these places are essential for people to relax and nurture social connections, and that the rise of auto sprawl and the loss of walkable neighborhoods all but ruined them.

Like Jane Jacobs’ classic work, the core thesis seems powerful and right. However, the books arguments are highly anecdotal and suffused with credibility-sucking nostalgia; the content on the role of gender and sexuality makes manifest the iffiness of his method.

The book describes the neighborhood taverns, beer gardens, cafes, and corner stores where many people used to stop for a while between home and work and spend time with a group of regulars, across class and age boundaries, with relatively low barriers to entry, the beverages as largely an excuse to socialize, and with conversation as the main entertainment.

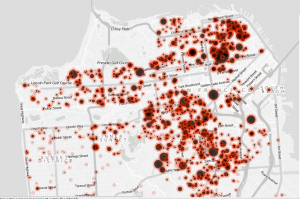

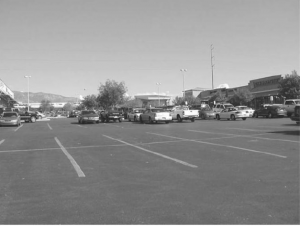

Oldenburg makes devastating arguments about the ways that automotive culture has greatly diminished third places. Low density, spread out single use zoning puts people outside of walking distance from commercial establishments and gathering places; so there are no “locals” where you’ll run into a regular cast of characters. Even successful places are patronized by roving groups of known friends, rather than stable sets who can assimilate newcomers. The corporate chains and malls that displaced local convenience stores, casual restaurants, and other gathering places are focused on efficient turnover of anonymous customers, and don’t provide the time and space for idle conversation.

Without the influence of a patient and hospitable patron, and a stable group who can entertain themselves endlessly with animated conversation over a beer or maybe two, and single sex or family crowd, bars become places for heavy drinking, with loud music, fads for entertainment, and pickup pairing.

Interestingly, Oldenburg’s attention to street life focuses on commercial establishments that extend onto the sidewalk, where people sit, eat, drink and chat. He does not focus on the semi-public domain of stoops and entrances where residents and proprietors hold court with passersby, which are Jane Jacobs tropes of healthy urban socialization and maintenance of social norms.

Without third places, people do 90% of their drinking and the vast majority of their entertainment within the walls of home; diminishing the mental health benefits that come from a broader social network, and putting excessive pressure on marriages. The age segregation of contemporary life, car-dependence, and pervasive scheduling makes life particularly dull and stressful for suburban youth and teenagers. The decline in the status and health of street life can be seen in the rise of terms such as “streetwise” meaning aggressive, self-protective and cynical, and the importance of activities at keeping kids off the street.

The depiction of “wholesome” “decent” tavern norms has a fair amount of “no-true-scotsman” about it. The centuries of urban life in which there have been commercial drinking establishments include numerous geographically distributed instances of culturally prevalent alcoholism and alcohol-fueled financially harmful gambling and violence. Prohibition was a mistake, but the temperance movement wasn’t driven by the zeal to ban taverns where men relaxed and chatted for an hour over one or two drinks.

The examples of social leveling, where physicians would spend time talking politics and sports with plumbers, seem real enough, but the book ignores the boundaries of ethnicity, sometimes religion, and especially race that would get the wrong kinds of people violently excluded. Not to mention, Oldenburg’s attraction to third places comes from a particularly situated class perspective – one reason he is so fond of third places is that they are more relaxing than stuffy cocktail parties where one must dress up and be on one’s best behavior, says the college professor who presumably is obligated to attend numerous cocktail parties.

The theorizing about gender is where the anecdotal method is most obviously saturated with cultural perspective. Oldenburg argues that one important role served by a third place providing is a relaxing single-sex refuge from heterosocial life (although some species of third place, such as the German beer garden, were populated by men, women, and children. The single sex socializing is important, says Oldenburg, for both men and women – various cultures have men only and women only spaces that are important for social life.

While Oldenburg acknowledges a need for female-only space, his language often takes a male perspective, e.g. “customers and their wives.” The book is replete with cavalier and confident statements about gender, such as “parenting is largely mothering”, “women have more spare time than men”, and “women don’t like snooker,” but unfortunately female guests must be allowed to take a turn. (I wonder what my female friends who are billiards aficionados think of snooker, which I had barely heard of). The assumptions about the lives of women are particularly class-coded – working class women always worked and never had idle time.

The book’s anecdotes about the disjoint sets of male and female interests are contradictory. One grown woman recalls that her interest in politics was stoked by adult conversations at the local soda fountain. At a “third place” in the UK, a woman who is passionate about cars is steered away from the men talking about cars to the women, because she will disrupt the natural male bonding around cars, and is best directed toward more feminine subjects of conversation.

Oldenburg deplores and bemoans a tendency toward companionate relationships with the growth of the college-educated professional class. “College men started to take their women took their women on hunting, fishing and boating trips” which ruined the ambience of the all male gatherings. The reason that mixed gatherings are unwelcome is that because with the tension that is necessary for sexual attraction, it is “impossible to relax with the opposite sex”, especially the forced mixing at dinner parties, and even a night out with one’s own spouse.

Meanwhile, all-male gatherings have no harmful effects. “Male groups encourage men to view women as sex objects but not treat them this way,” as we surely know from fraternities and technology conferences. The interest of women in gaining access to the all-male clubs that are key venues for business and political networking is described as “The blood lust of feminists seeking to invade or destroy.”

And, Oldenburg assures us, homosocial bonding has no connection to homosexuality. “Eroticism is almost always absent in all male groups”, and rather, “homosexuality becomes common when male bonding is weak.” Pause for laughter.

Oldenburg’s observations and assessments about gender are full of culturally situated stereotypes, not to mention rampant sexism. The dominance of dubious assumptions about gender raises questions about other observations in the book. Unlike the work of, say, Jan Gehl, which is based on meticulous observations of social life in public places, and a long history of design experiments to affect the social life in public spaces, Oldenburg’s book is full of one-off personal observations and retold anecdotes.

Because of Oldenburg’s strong opinions and heavily anecdotal methods, I would also wonder about counter examples where car cultures may have created functioning third places – what diners, beaches, and other car-dependent locations still fostered informal socializing with regular participants. The book is also wholly secular; there may be evidence and arguments about the relative roles of churches and synagogues in fostering regularly attended gatherings that nurture social ties (although Charles Marohn of Strong Towns argues that suburban churches also weaken the third place nature of community events).

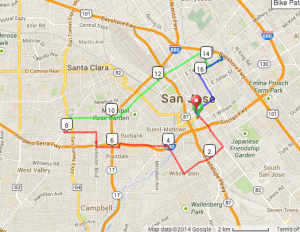

Thinking about the book, I wonder whether bike party rides count as effective third places. They’re not daily, but with test rides there are weekly events, they involve casual socializing with people across a range of ethnicity, income, and age, with alcohol etc as social lubricants, and sets of regulars who are open to newcomers. They use suburban people-unfriendly arterial roads and parking lots, and convert them into sociable parades and festivals.

Interestingly, a quick Google search shows that in addition to planners, Christian bloggers have apparently taken up consideration of Oldenburg’s work. Church folk wonder whether religious institutions can provide “third place” style gathering spots, or bring church practices to “third places”, or possibly compete with secular places.

Oldenburg himself is dismissive of the ability of online services to play the role of “third places”, and stresses the need for in-person interaction. However, this perspective neglects the increasingly common interaction of online settings, where people can chitchat and meet virtually through others with similar interests and mutual friends, and in-person gatherings that spring from online discussion.

While Oldenburg’s methods are highly qualitative and culturally situated there is some good evidence that Oldenburg got key points measurably right – greatly reduced time spent socializing informally outside of the home; the dramatic increase in the structure of children’s lives and reduction of outdoor self-directed free play.

When the book was written in the 90s, Oldenburg writes that the planning profession had paid negligible attention to community spaces. The government was well established in the business of creating outdoor parks for recreation, but played minimal roles in creating spaces for urban socializing. (Oldenburg omits discussion of the compulsory and largely disastrous civic and office plazas created in the second half of the the 20th century. William Whyte’s detailed study of the success factors for public plazas in New York City is the exception that proves the rule).

Since then, however, the planning and design professions have accelerated study of public places and have started to seek to foster lively public space, and civic participation in the creation of public spaces, on a more regular basis. The Project for Public Spaces, founded to build on Whyte’s work, has developed a global practice in the field in recent decades, and cites Oldenburg as an inspiration. Jan Gehl’s firm has been influential in transforming places around the world, including Copenhagen, Melbourne, and New York City.

With these practices, the role of the public sector is to foster the places that can foster social interaction. Outdoors, this includes human-scaled plazas with detail fostering social interaction, and sizeable sidewalks taking space back from vehicles. For indoor spaces, the public sector is starting to play a role in fixing the policies that caused third places to decline – once again allowing mixed use zoning, and walkable densities, so people can live near coffeeshops, restaurants and convenience stores; and changing vehicle parking laws so that driving and parking does not make it unpleasant to stroll by a neighborhood place.

The revival of big cities and small city downtowns, and neighborhood design encourages optimism about the opportunity to gradually bring back third places. As of Oldenburg’s sequel, it didn’t seem like much progress had been made – the Great Good Places he was able to find in a late 90s anthology were , However, the drastic shortage of increasingly popular walkable places is causing gentrification, and raises the risk that until and unless the shortage is filled, the social and civic capital available to people with public places will be less available to lower income people exiled to exurban sprawl.