Who gets a thrill from the being mayor of their local coffee shop? According to a recent Forrester study the users of location-based services (such as FourSquare, Gowalla, and, Brightkite) are 80% male and 70% are aged 19-35. Usage is concentrated among a relatively small number of very heavy users: “only 1% of those that use them do so more than once per week” – but this tiny minority has accounted for over 100 million checkins to FourSquare, the current leader in the space.

Does this narrow appeal mean that location-based services are a fad? In a quote in the Read Write Web article linked above, FourSquare founder Dennis Crowley makes the case that tech-savvy young men are early adopters and leading indicators for a broader market. This often true, but leaves out another potentially important distinction. The addictive feature of FourSquare for those who love it is the competitive game dynamics – the ability to be annointed mayor of the local bar or coffee shop. Based on the numbers, this win/lose competition is addictively appealing to a small number of mostly young men, leaving many others cold. Of course, people are all individuals, gender trends don’t determine individual preferences; there are women who love FourSquare competition, and men who don’t see the appeal – the point is that the numbers show that the FourSquare dynamic has a narrow appeal.

FourSquare has recently been adding a greater diversity of badges, for events like the World Cup and ComicCon, brands including Louis Vuitton and Intel, travel-related services like Zagat’s and San Francisco BART. But the core dynamic is still competitive, and that is limiting it’s appeal. Last fall, I wrote about how FourSquare’s conflicting social incentives – to meet up with friends and to defeat them – leave me cold. It seems like there are more people who aren’t yet attracted by the desire to be the Mayor of Potrero Safeway (no offense, tweet or comment if you know who you are).

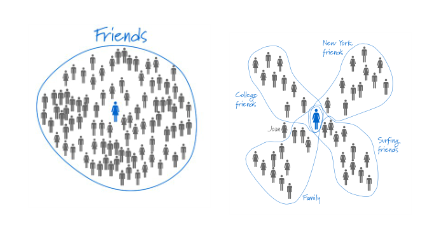

When adding game dynamics to software, it’s important to consider the varying motivations of potential users. I expect that over time, location-based services will be developed with affordances for a wider variety of motivations – social connections, group affiliations, geographical exploration, product promotions, loyalty programs and more. The different affordances will help location-based services appeal to people who have motivations other than competition, and to demographics broader than FourSquare’s core participant base of young men.

So, does the current narrow appeal mean that marketers should forego FourSquare and the location-based trend? Probably not, but they should be sensitive to the design of their program, the social motivations the program cultivates, and the relation between those motivations and their intended customer base.