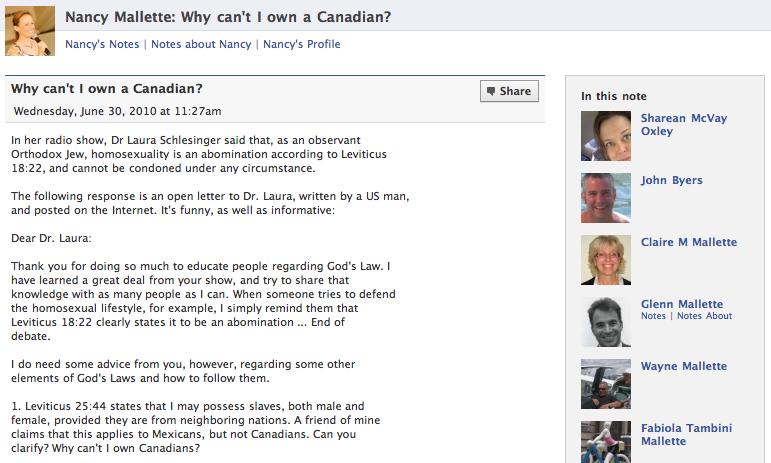

As the dominant online social network, Facebook is place where activists and organizers head to help their movements and ideas spread. People are already on Facebook, and can share discussions, events, actions, with their networks of friends. This is great. But there’s a pretty serious problem, it seems to me, in the use of Facebook for organizing. It’s hard to get to know people on Facebook.

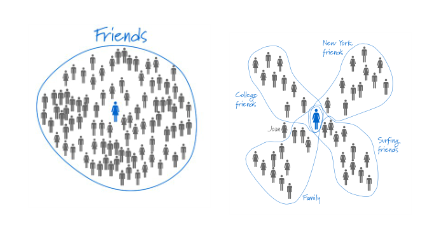

In the Facebook social model, it’s not very socially acceptable to “friend” someone you don’t actually know. The Facebook model is designed for people who are already “friends”. A “friend” relationship is symmetrical – both need to acknowledge the relationship. Facebook does have a separate built-in asymmetrical type of relationship. Institutions or celebrities can create “pages” that fans can “like”. The model sets up a hard dichotomy between people, who have friends, and celebrities who have fans. It doesn’t make social sense for a celebrity or institution to “like” one of its fans. By contrast, in Twitter, it is easy and socially acceptable to follow someone without their following you back. With this affordance and social practice, it is easy to become familiar with someone’s tweets, and use lightweight social gestures including retweets and replies to over time get their attention and make their acquaintance.

On Twitter, there is no hard dichotomy between friend, aquaintance, and fan. There are celebrities on Twitter who have millions of fans, and that relationship is clearly not mutual – you are probably not friends with John Mayer or Ashton Kutscher. But on Twitter, the follow affordance is the same, allowing for nuance and gradual change. On Twitter, and in a blog or forum communities with shared discussion where people use stable handles, individuals can become familiar with others over time.

In Facebook, if you don’t know someone already, you might come across them in conversations in the discussion thread started by a friend, or the page of an institution that you “like”. But you then have no good way of finding more about them, and gradually making their acquaintance, since many public profiles are quite sparse, and stream that really gives you a picture of the person is often locked down for privacy. And (at least I find) that it is awkward to address someone you don’t know, even if you’re a conversation started by the post of a mutual friend.

Facebook does have an interesting feature and social practice that helps someone convene a conversation. When you post to Facebook, you can “tag” a set Facebook friends to notify and call them into the conversation. Oakland Local’s community manager Kwan Booth describes using this technique for jumpstarting conversations with Oakland Local. Even if those friends don’t know each other, by virtue of being invited to the conversation by a host, they have been given implicit permission and encouragement to talk to each other. When you’re tagged, it feels less awkward to directly address a fellow tag invitee whom you didn’t know before. But still, you don’t have a good way to get to know these people over time.

For organizers, it is valuable to use Facebook to enable information and actions to spread throughout people’s existing networks of friends and family. But for organizers it is also often very important to build a greater sense of community, and cultivate the network of relationships in the community. Helping people get to know each other is important to growing a sense of shared purpose, reducing feelings of isolation and disempowerment, build on people’s social motivations to take action.

Much of traditional marketing has been focused on attracting individuals to a brand; even social media marketing seems to focus on building a relationship between an organization and its customers and constituents. Thus, coaching about how to stimulate conversations on Facebook pages about topics relating to your organization and your brand. But organizing isn’t just about the relationship of people to your organization, but about their relationships to each other.

In Facebook, where conversations remain in existing cliques and friend networks, it seems much harder to grow the network of relationships. Ethan Zuckerman talks about this issue in this CNN article – does the dynamic of Facebook’s social network, based on existing relationships, make it harder to make new connections. In The Networked Nonprofit, Beth Kanter and Allison Fine talk about the role of “network weavers” who combine traditional and online skills to connect people and organizations; in Share This, Deanna Zandt talks about using social media to deliberately get to know people with diverse cultural backgrounds. But how do you do this using a tool that makes it hard for people to get to know each other?

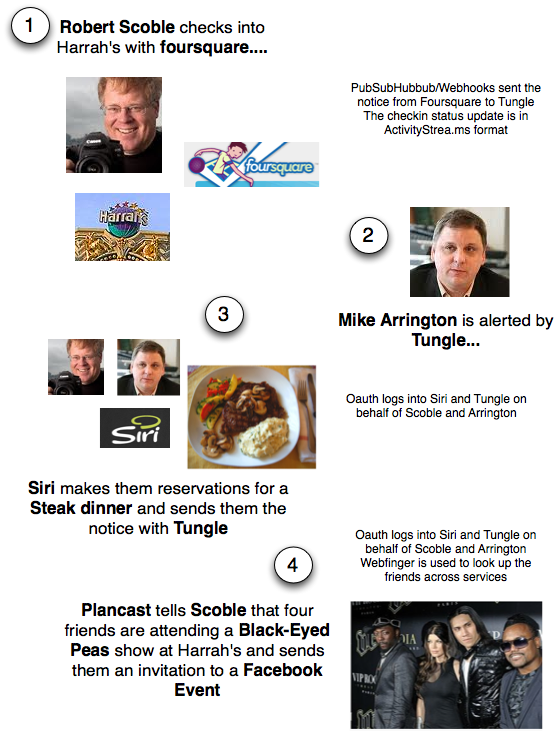

One way to get around Facebook’s limitations – and an important tool for any community that participates online – is to meet up in person. An organization or organizer can convene meetups and conferences. There, people can meet in person, and after meeting each others’ acquaintance, go back and “friend” each other on Facebook. It’s become quite common for in-person meetings to evolve online acquaintances into closer connections; the inperson connection and online reinforce each other. I’ve met up with Twitter acquaintances at conferences and on vacation. The BlogHer conferences brings together women bloggers, and the Netroots Nation conference developed as a meetup for the Daily Kos political blog online community.

But in more socially open networks, the in-person meetup bolsters a process of getting to know each other that also progress gradually online. With Facebook, there’s a much higher hurdle until and unless you’ve met in person. This is particularly challenging for geographically distributed communities – spread out regions like the Bay Area, or interest groups and movements that are spread out around a country or around the world.

A question for organizers and activists reading this post – do you use Facebook for building community, and if so what practices do you use for this? Have you developed practices for integrating Facebook into a broader set of tools and practices for people to meet each other, and if so how?

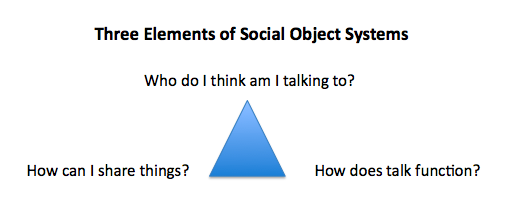

p.s. I’m using the term “social model” to refer to the affordances and conventions of recognizing, meeting, getting to know, and affiliating with other people. I’ve talked about this concept as it relates to social software design in posts including here and here. There may be better terms for this concept. If you know of better terms and references, please leave a comment.