Recently I read two good books of environmental history about two different places that are rediscovering the value of wet places. The Big Muddy by Christopher Morris examines the history of the lower Mississippi; Down By the Bay by Matthew Booker explores episodes in the history of the San Francisco Bay.

In both places, prior to European settlement, Native Americans lived off the rich wetlands ecosystems over long periods of time. The known history on the Mississippi was more complex, with native civilizations shifting among combinations of foraging and agriculture. The cultures in the different places used the shifting cycles of wet and dry, using different food sources at different times, and spending time on high ground in wet seasons.

In both places, when Americans took over from earlier European colonial settlement, they did not value wetlands; they did not even comprehend them as places that are part wet and part dry. Instead, they saw land that was excessively wet, that they invested in drying out and filling in; and they saw water that was chaotic and destructive, that they sought to tame and navigate. The efforts to turn the Mississippi’s floodplain into dry and highly productive agricultural land; the efforts to create farmland from the Bay Delta; to build San Francisco on fill carved out of hills and dredged from the bay; and to tame regular floods, took multiple iterations.

There has been plenty of environmental damage from oil and chemical industries in the Mississippi Delta, but that is not the focus of the Big Muddy. Down By The Bay talks more about the impact of industry on the Bay. Hydraulic mining in the Sierras in the late 1800s had catastrophic impacts, washing down millions of tons of mountainside sediment into the Delta and Bay, causing massive ecological destruction and leaving toxic mercury that remains on Bay floor causing trouble until today. Oil refining and chemical industries have left legacies of toxic pollution in the Bay

Flood protection, the failure of walls as the dominant means of flood protection, and the problems with the concept of flood protection, are key themes of the Big Muddy. Down By the Bay discusses flood protection in the SF Bay Delta as one of several thematic segments on the environmental history of the Bay; but the book doesn’t go into depth on the vulnerability of Delta levees, the ongoing, severe and unresolved conflicts between the Delta’s roles as estuary, fishery, agricultural center and water source for dry parts of California. The California book also doesn’t touch the issues of flooding and flood protection efforts at the Bay’s many tributary creeks, most of which have been channelized.

Both books, in telling the story of the conversion of formerly wet places for massive scale agriculture, also tell the stories of exploitative labor practices; the relatively familiar stories of slavery, share-cropping, and forced levee labor in the south, which are more horrible with more historical detail; and the perhaps less-familiar stories of exploited Chinese immigrant laborers in California. In addition, Down By the Bay focuses on the change from Native American traditions of common land, and Spanish traditions considering tidal areas to be common land, to United States traditions of private property, enclosing the formerly common area for large-scale private advantage.

Only relatively recently have Americans started to understand the unintended consequences of draining wetlands, to understand the value of the partly wet places as rich, self-renewing, resilient ecosystems, and started trying to recapture some of that value in an environment that has been already transformed to a vast extent.

The lower Mississippi has been heavily agricultural; as its capacity for industrial crops declined, some places are starting to turn to a potentially more sustainable mix of rice and fish ponds. There is growing awareness on the Mississippi about how the loss of wetlands has increased coastal erosion and vulnerability to flooding and storms; there are incremental efforts to recreate hardwood forests in some floodplain areas. . Restoration efforts are proceeding incrementally in the heavily leveed, channelized and polluted Mississippi. It is not clear how much will there is, and how feasible it would be to create more somewhat more flexible responses to the river’s flood cycles.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, the initiatives to reestablish wetlands have been driven by an environmentalist perspective seeing the bay as a natural habitat to be protected from humans and to be enjoyed by watching. Booker incorporates many assumptions of ecological science and environmentalism, including attentiveness to the richness of wetlands ecosystems, value for ways that native cultures adapted and flourished in partly-wet places, and displeasure with ways that industrial society uses up and poisons ecosystems.

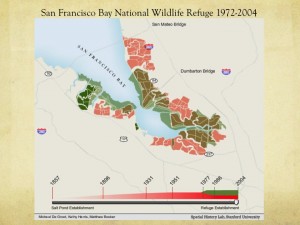

But Booker is somewhat skeptical of the idea of “restoration.” One of the key indicator species used to test whether the Bay ecosystem is reviving is a soft-shelled clam originally imported from the Atlantic. The success of industrial salt flats at providing habitat for migrating birds, now adopted as the foundation of the Bay’s wildlife refuge, was a happy accident. Booker writes about concerns that the presence of mercury at the Bay floor may prevent the reopening of former salt ponds to tidal flow because of the risk of disturbing mercury in sediments, increasing conversion of mercury to highly toxic methylated form, and harming wildlife. Since that chapter of the book was written, the South Bay restoration project has gone ahead and opened a few areas to tidal flows, while carefully monitoring for toxicity. Booker argues that it is nostalgic, but not really possible to return to a past era.

Booker also is critical of the middle-class environmentalist perspective of nature and open space as views to be consumed. The hiking, kayaking, bird-watching, and other outdoor recreational activities are leisure options enjoyed by the middle class and wealthy; activities where people engage with the natural world for sustenance by fishing, gathering mollusks, hunting, etc are marginalized. Booker believes that people will really have regained a relationship with the Bay when humans can be part of the food chain.

The Mississippi efforts to recognize the value of wetlands and adapt to a wetlands environment may be less ideologically environmentalist and even more fragmentary in scale, but the rice/fish ponds and bottomlands hardwood forests incorporate people as participants in the ecosystem.